“Each piece of sushi costs $10?” My father couldn’t believe it.

His first shock was at the price of the meal: $150. The next shock was that it wasn’t “all you can eat.” It was $150 for 15 courses—and each course was just one piece of sushi.

Since I was young, my parents never understood why people ate sushi at restaurants. “It’s just fish on top of rice,” my mom would say. Our only exposure to it outside the home was at Chinese buffets, serving low-quality rolls and nigiri. At home, she’d wrap cucumber, egg, fake crab meat, and rice in nori and call it sushi, even though I insisted it was more like Korean gimbap, if anything.

I’d heard of some wealthy Georgetown students splurge at Nobu for fancy anniversaries. But I didn’t get it until I tried counter omakase at Sushi W for myself. It was more than just a sit-down meal. It was an engaging party of the senses.

Many articles have attempted to tackle the question of “why is omakase so expensive?” Relying on chef, food expert, and customer interviews and anecdotes, each person has a different answer. Hence, I attempt to tackle this question with a comprehensive, structured approach, relying on business and economic frameworks:1

Restaurant profitability

Pricing strategy

Market dynamics

Restaurant Profitability

Using a typical profitability framework, I mapped the factors that omakase restaurants consider when trying to maximize their success.

On the revenue side, the pricing strategy can greatly inflate the price of an omakase meal. Moreover, there is increasing demand for omakase due to its perceived perception as a status symbol and a part of a refined, worldly palate (as evidenced by more references to the fish by their Japanese names, instead of the American translation). The supply of omakase has competing effects. On the one hand, there are more Japanese sushi chefs in the U.S. than before, and new sushi restaurants are popping up left and right. On the other hand, the market is still oligopolistic: the chef gets to control the price with a set menu, restaurants have limited seating (both to create an exclusive effect, and also because of logistical capacity constraints), there’s the time constraint in that most restaurants are only open from 5pm-11pm, and there is a limited amount of fish available for import.

Costs are high throughout the supply chain. Before we even begin to consider the actual labor cost associated with a meal, many chefs train for years and there is an expectation that they can be “paid back” for their time investment. Variable costs associated with raw ingredients (high quality fish from the Tsukiji Fish Market, where bargain occurs before sunrise), importing those ingredients from Tokyo, then preparing the fish, are also high.

Menus often contain rare seafoods such as Golden Oscietra caviar, A5 wagyu from Kagoshima, sea urchin from Hokkaido, Alba white truffles, and Akamatsu. Recently, some fish prices have increased. For instance, the cost of uni increased from $80/lb to $300. The seasoning is also expensive: real Wasabi (not the fake radish kind) is around $200/lb.

Then, it takes a long time to prepare the fish:

The fish arrive at 10 a.m., and it takes time to clean the fish and prepare it for the night. This is very labor-intensive work.” Perez Miranda says preparing the fish is such meticulous work that he can only order enough fish to serve 50 people a day, which is why the deliveries are so frequent.

Finally, being a sushi chef is just hard, especially when you have to prepare the food in front of the customer.

Pricing strategy

Using value-based pricing, omakase restaurants charge what they believe customers are willing to pay. This typically encompasses the tangible costs that go into making the meal, and a premium that customers are willing to pay above that, based on intangible factors related to the chef (i.e. culinary talent, cooking techniques, and menu and ingredient selection), and the customer dining experience that introduces multisensory components and an element of novelty with each course, and signaling effects.

Hence, customers’ willingness to pay in part represents the appreciation and trust they have in the chef’s artistry—to go beyond just a cook, instead using their extensive past knowledge of sushi to curate a unique experience in the present. After all, the chef chooses whether fish is served raw or seared, fresh or aged, as nigiri or as a handroll. They also select the seasonings and flavorings to be folded into the sushi; dipping it in extra sauces is considered an insult to the chef.2

Market Dynamics

Another part of the premium is signaling effects. Omakase is a luxury good. Some might consider it a Veblen good, which higher prices increases demand for them because they are consumed as status symbols. There are two reasons people consume Veblen goods:

Pecuniary emulation: when a member of a lower class tries to signal that they belong to a higher class

Invidious distinction: when a member of a higher class consumes to show that they are different from the lower class

With the recent craze in omakase, I would argue that its consumption is mostly the former. Upper-middle class, young professionals like to show they have the disposable income and refined palate to indulge in a 15-course meal of (mostly) raw seafood, without needing to order specific rolls. California rolls? Who’s she?

Because there are only so many Japanese sushi chefs in the U.S. specializing in omakase, the market is oligopolistic. Most restaurants charge about $150, and it’s hard to find anything lower.

Nonetheless, some price variation still exists. At Sushi W, you can get a lunch special for $38 and premium dinner for $68; meanwhile, Masa, a 3-star Michelin, charges $950.

These are some of the factors that allow certain restaurants to charge more or less than others:

Newer chefs versus celebrity chefs. Taking a look at Masa’s website, they emphasize Chef Masa’s story and accolades. Their Instagram is also just the chef’s personal instagram. Meanwhile, Sushi W has an Instagram for their restaurant and highlights newer chefs.

Differentiation as premium or value experience. Sushi W prides itself in being affordable. It seems to be targeting newbies, as its website has an explanation for what omakase is and a FAQ page. Masa is targeting experienced diners who want the cream of the crop experience. Hence, Sushi W is treating omakase as a normal good — the more affordable, the more demand. Meanwhile, Masa is treating omakase as a Veblen good, for upper class diners who want to perform invidious distinction.

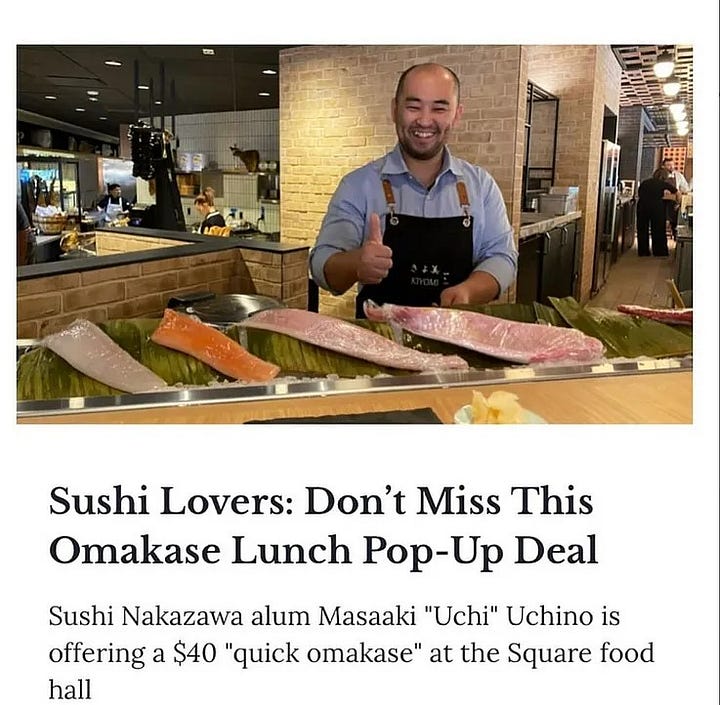

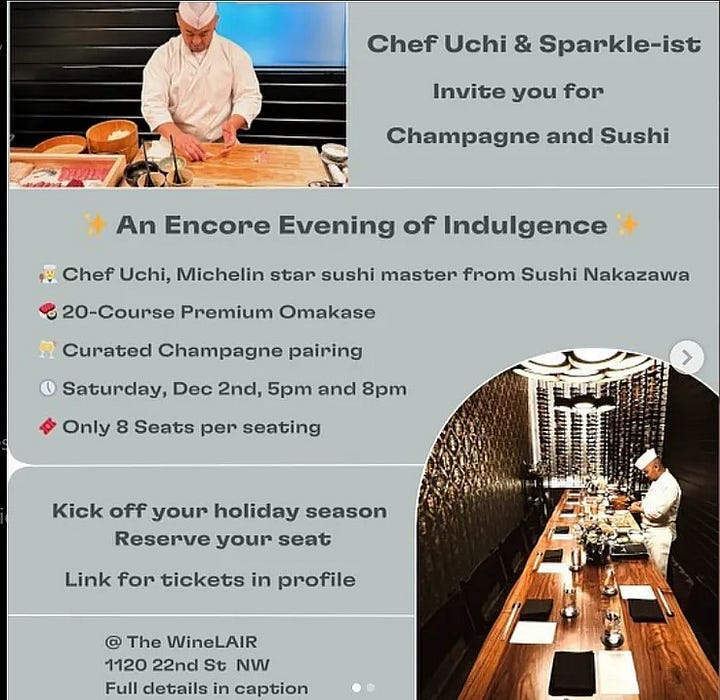

Menu curation (types of fish offered, cooking techniques, number of courses). Chefs can choose whether they want a simple or upscale menu, also with the target customer in mind. Chef Uchi, a DC-based chef, has a popup in a food hall that offers $40 30-minute lunches with 8 courses. However, he also does a 20-course premium omakase and champagne pairing for $375.

Ambience. The pop up is in a brightly lit food hall where office workers frequent during lunch hour and occupies another restaurant’s counter space. The premium night is in a private wine club with dim lighting and intimate seating.

The social media marketing language clearly shows the difference between a value experience (highlighting the food and affordability) and a premium one (highlighting the chef and the exclusivity):

Clearly, the question we should be asking is not, “why is omakase so expensive?” It’s “why are customers willing to pay such high prices for omakase?” We can then model the customer’s willingness to pay using the following regression equation:

Where beta_0 is the baseline costs associated with making a meal, “chef” is the chef attributes (i.e. culinary talent, cooking techniques, and menu and ingredient selection), and “customer” is the customer satisfaction (dining experience, pleasure from novelty, signaling effects).3

In omakase, there is no “you get what you pay for.” It’ll always be, “you pay for what you get.” Hence, a customer’s willingness to pay actually represents their level of trust in the chef to deliver an experience that maximizes the customer’s satisfaction. After all, the literal meaning of omakase is “I’ll leave it up to you.”

There were a few ways I thought about segmentation: tangible vs non-tangible factors, front-end vs back-end factors, etc. However, I ultimately decided to use these three frameworks.

This is also the difference between AI generated art, which can be tailored by prompts, and buying a finished piece of art from an artist.

This model isn’t perfect, since a better chef can result in more customer satisfaction. Hence, the chef variable exists in the equation to serve as a control. There’s potentially an interaction effect, in which a “good” chef results in a greater willingness to pay for every increase in customer satisfaction: